Strategically engage key partners

Policy theory research often focuses on increasing policy makers' access to evidence as a way to avoid taking shortcuts, like making decisions based on emotion. Implementation science suggests that increasing access to evidence is not enough, and that policy change should be examined in the wider context of debate, coalition forming, and persuasion. Meaningful policy change requires “a long-term strategy to form alliances and develop knowledge of policy makers and policy making," rather than using evidence in policy making on an ad hoc or one-off basis.

Understanding networks and systems is important to develop sustainable policy change. This section is meant to help readers take the steps to build engagement strategies for partners that represent different systems and networks. Engagement should be an ongoing process of connecting people to one another and to an issue. Engagement should not be in name only - we have all experienced engagement activities that give people a specific role to play that leads to a neat, predictable outcome. According to the "Build With" movement, undervaluing and underinvesting in engagement strategies can lead to a disconnect of certain individuals or groups, and mistrust of government. When developing engagement activities, remember that how people engage and whether they engage has to do with how you structure opportunities for engagement.

Convene a core advisory group

An advisory group comprised of people from multiple sectors can be helpful as you consider the local social, environmental, and political context in which you intend to introduce policy change. Revisit your stakeholder map, and determine who would be best to serve on this group. To make sure you are considering the problems and solutions through an equity lens, include people with lived experience who have expertise in the effectiveness of systems, whether those systems function as intended, and how they may impact human behavior. You may also wish to include someone with experience working with data and analysis - this person can help determine the type of data that may be readily available and useful to collect, and can also help plan and shape your analysis to figure out which programs are effective. Be sure to invite front-line workers as well - it's critical that whatever solutions come out of this process are meaningful to those who will be responsible for implementing them.

Bringing people together can be challenging, but there are a few ways to set and manage expectations. First, make sure that the group is aware of the problem statement, current state, and future state - this can help start everyone off on the same page. Next, spend some time getting to know each other’s work to learn about everyone's strengths. This shared understanding can help as you clarify roles and responsibilities of each partner in the group -- this is important to avoid finger-pointing in the future, and to ensure that none of the tasks slip through the cracks. In some cases, there are many actors with different responsibilities, as in the case of Baltimore City's 38-member Youth Fund Task Force, which is chaired by nonprofit and corporate partners and includes representatives from the nonprofit and faith communities; students; the business sector; local universities; City Council; and the Mayors Office.

Once roles and responsibilities are clear, you may consider developing a charter, guidelines, or terms of reference to set expectations for the group. Be sure to distinguish this from other boards and commissions that your city may have. Next, you may wish to establish a regular, ongoing meeting schedule. Be sure to send agendas and meeting materials ahead of time, and clarify the objective of each meeting.

In Seattle, the City developed its Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda (HALA) to respond to rising housing costs and homelessness. This is a trend in other west coast cities as well, which may be explained by an influx of new residents who are attracted by the emergence of tech jobs, the attraction of the outdoor lifestyle, or the recent passage of progressive policies like legalized gay marriage, a $15 minimum wage, and legalization of marijuana. Seattle brought together a multi-stakeholder advisory group comprised of local housing experts, renters and homeowners, developers, and government officials to share information about their needs, and develop recommendations based on these needs. The interests and motivations of this group were varied, and it took about ten months to find common ground. The series of recommendations that the advisory group created is meant to serve residents with a spectrum of needs.

Build a process for community participation

Of course, not everyone can be included in an advisory group, and advisory group members may not necessarily represent the varied perspectives of their peers - for instance, not every homeowner has the same set of needs. To gather input from a wider swath of the population, it can be helpful to build a process to invite the public at large to share their ideas. Cities do this in a variety of ways, from online conversations and surveys to in-person meetings. Remember that being intentional about gathering the viewpoints of people is more important than using the latest technology and tools.

The insight generated by community participation exercises can be included in your review of evidence, which is discussed in a subsequent chapter. In West Virginia, a state that has been hit hard by the opioid epidemic, state health officials drafted an opioid response plan that was informed by public engagement, as well as local and regional subject matter experts. The public was invited to present comments on ideas for decreasing overdose, early intervention, treatment, and recovery. Public health and medical faculty from West Virginia University, Marshall University, and Johns Hopkins University provided responses to the comments. The result was an Opioid Response Plan that health commissioner Rahul Gupta presented to Governor Jim Justice.

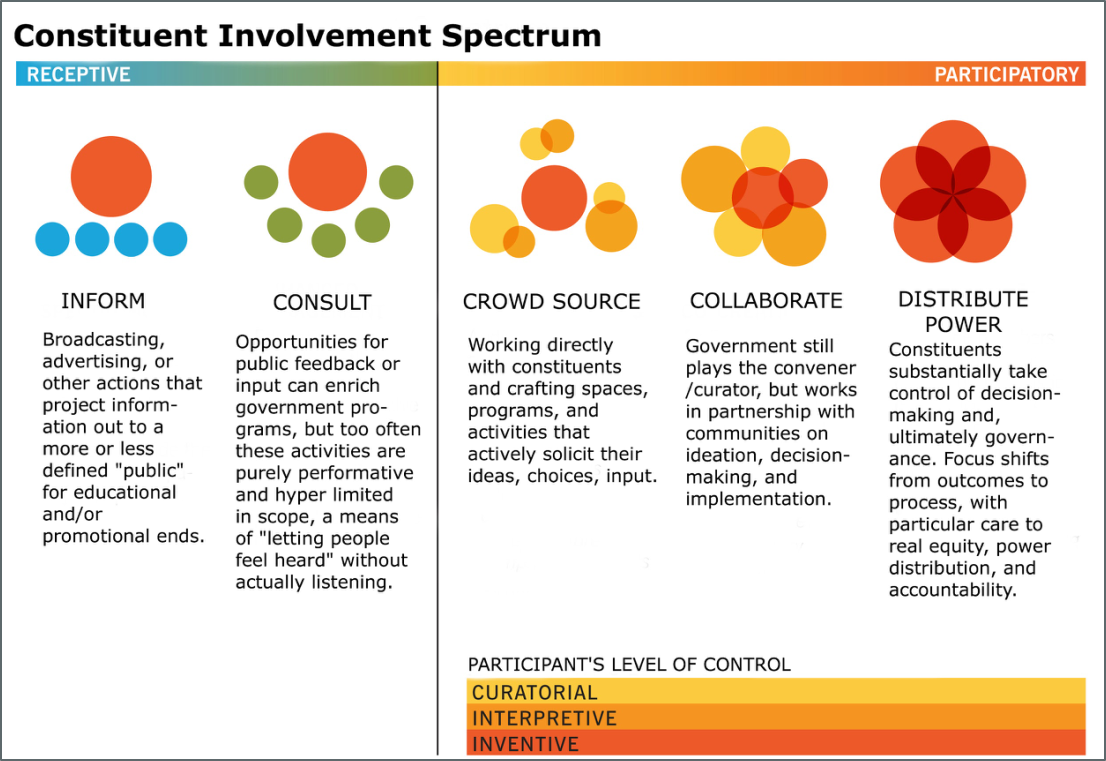

A sample spectrum to plan your own community participation process, created by Laurenellen McCann, is below. Source: Laurenellen McCann

Source: Laurenellen McCann

Community-based participatory research is another way to work with the community to improve outcomes. CBPR means the community is involved in all aspects of the research process, which is often iterative. In CBPR, traditional researchers and community members share knowledge as well as resources and credit.

CBPR In Action: In San Francisco, an environmental justice nonprofit teamed up with the City's Department of Public Health and an outside evaluator to understand the root causes of obesity and food insecurity in low-income neighborhoods, and identify solutions. Through research methods such as interviewing residents and store owners, diagramming store shelves, GIS mapping, an economic analysis, and review of similar policies in nearby cities, the team observed that the stores that residents hasve access to were stocked with less healthy foods, and that residents wanted more healthy food, and less alcohol and tobacco. This project resulted in local and state legislation to encourage stores to stock fresh produce.

Develop relationships with subject matter experts

One way to keep subject matter experts engaged is to involve them in the community participation process, as described above. In the West Virginia example, subject matter experts responded to and synthesized the public comments. Other opportunities are described below:

Advisory: A city department head, Mayor, or staff member may develop a one-on-one advisory relationship with university faculty member, or a collaborative between the City and University to address a particular problem. A great place to start is to look for relevant practice centers within your local university, and reaching out to subject matter experts. In addition to their expertise on the relevant policy topic, he or she may also be able to identify other experts, and even provide support on hiring the right talent to lead certain programs. An advisory relationship with a university subject matter expert can also help when cities are considering bringing in new programs. These experts are often familiar with programs that are based on national models, and can provide insight into a program's origin and lineage, effectiveness in other places, and the potential for implementation in your city. Academics can also help identify indicators based on government indicators or literature. Finally, relationships between policymakers and researchers provide the most broadly effective route to pulling research into policy.

Research and evaluation: Academic experts may support cities in evaluation - indeed, evaluating city initiatives is a traditional model of city/university relationships. Sharing the information you collected in the "Gather Information" phase can help researchers understand your work and goals, which in turn will strengthen the support that they can provide. Discussing details about your intervention and evaluation plan at the beginning of the process means that a research partner can help with the evaluation design and data collection. For instance, the Wilson Sheehan Lab for Economic Opportunities walks cities through considering the following questions before partnering on an evaluation:

Is there a clear policy/program model with objective screening criteria?

Is it possible to evaluate what happens both with the policy/program and in the absence of the policy/program?

Are there one or more measurable outcomes of interest?

Are there enough people for rigorous quantitative analysis?

What data will be necessary for the study, and what are the processes for accessing these data source(s)?

Is there a compelling reason to evaluate?

In addition to assessing readiness to conduct an evaluation, researchers can help you hone in on the purpose of the evaluation. The World Bank describes several potential uses of evaluation which are defined here. In brief, evaluation can help decision makers:

- make resource allocation decisions

- rethink root causes of problems

- identify new problems

- decide on a best alternative

- determine whether programs or policies are being implemented with fidelity

- determine whether programs or policies are having the desired impact

Researchers can also provide support in sharing the results with the scientific community through papers and conferences, which is valuable in creating a peer network of evidence-based city practitioners.

Training and technical assistance: University partners, especially those at practice centers, can be helpful in developing or updating training curriculum, training the trainer, and delivering training to city staff.